On January 13, 2020, the IRS published in the Federal Register the final regulations on Opportunity Zones (OZs), “Investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds.” And they were, for the most part, good news for OZ investors, qualified opportunity funds (QOFs), and qualified opportunity zone businesses (QOZBs).

So where are we now with what is considered by many to be a “once-in-a-generation” wealth-creating program?

The Bad News

The bad news is 10% vs. 15% Basis Step-Up on the Invested Capital Gain.

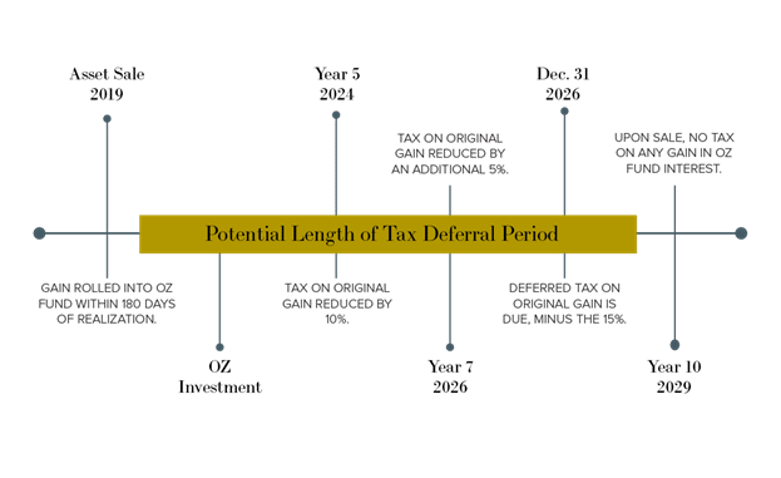

As of now, 2019 has come and gone, which means that if you didn’t invest and defer a capital gain into a QOF by December 31, 2019, the maximum amount of basis Step-up for that capital gain is now 10% instead of 15%. This is because the OZ invested capital gain will become due with the taxpayer’s 2016 tax return, which is six and not seven years from 2020. Please refer to the diagram below:

The program allows for a 10% step-up in basis if the investment is held for five years and an additional 5% basis step-up if held for seven years. Thus, if a taxpayer has yet to invest a capital gain, he/she/it has until the end of 2021 to take advantage of the five-year 10% step-up, but unfortunately no longer has the ability to take advantage of the additional 5% basis step-up.

California and the Other States Either Not or Partially Conforming

Unfortunately for California investors, the state has not yet conformed with the OZ program. Mississippi and North Carolina are the two states that do not conform. This means that investors from these three States will have to pay State capital gains tax during the year taxpayer invests the capital gain in an OZ.

Arkansas, Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania have partially conformed, either restricting the investment to the State’s specific OZs (Arkansas and Hawaii) or for the individual corporate taxpayer only (Massachusetts allows only for corporate taxpayers to take advantage of the program, while Pennsylvania only allows for individuals).

The rest of the States either fully conform or do not have a capital gains tax in the first place.

The Good News

The final regulation on OZs (December 2019) brought about some very beneficial changes from the previous two sets of proposed regulations (October 2018 and May 2019, respectively). I’ve highlighted four of these beneficial changes below.

Gross 1231 Gains Are Qualified Capital Gains

Capital gains from IRC Section 1231 property (depreciable or real property that is used in a taxpayer’s trade or business and held for more than one year) qualify for OZ investing. Under general tax rules, a taxpayer calculates a net Section 1231 gain or loss at the end of the year. If there is a net Section 1231 gain, then it is taxed at capital gains rates; if there is a net Section 1231 loss, the loss is characterized as an ordinary loss and may offset regular taxable income.

Under the May 2019 proposed regulations, only net Section 1231 gains were treated as eligible gains for OZ investing. As a result, a taxpayer’s 180-day period for investment into a QOF did not begin until the end of the year when the amount of net Section 1231 gain could be determined.

The final regulations, however, allow a “gross approach” for Section 1231 gains whereby eligible gains now include the gross amount of Section 1231 gains unreduced by Section 1231 losses. As a result, an investor doesn’t have to wait until the end of the taxable year to start the 180-day period, and the investor can commence the 180-day period the date of the sale or exchange that give rise to the eligible Section 1231 gain.

Under the final regulations, by default, the 180-day period begins on the last day of the partnership taxable year, but the partner may elect to instead use: (i) the same 180-day period as the partnership; or (ii) the due date for the partnership’s tax return, without extensions. This change give partners additional time to receive Schedules K-1, which provide partners with necessary information about the amount of their distributive share of eligible gain.

Doubling of the Working Capital Safe Harbor Period

Prior to the final regulations, a QOZB had a 31-month safe harbor period for deployed working capital before the QOZB was required to be engaged in an active trade or business under IRC Section 162. This presented issues for the startup businesses as well as for very large, transformational projects.

The final regulations doubled the safe harbor period to 62 months. Thus, tangible property that is purchased, leased, or improved during this 62-month period will count toward the 70% tangible property test, and intangible property purchased or licensed during that period will count toward the 40% intangible property use test.

Aggregation Allowed for the Substantial Improvement Test

Prior to the final regulations, it was understood that in order to meet the substantial improvement test (i.e., doubling the fair market value of non-original use property acquired in an OZ), the investor would need to spend at least the same amount of money acquiring the property to renovate or improve the non-original use property.

The final regulations allow for a taxpayer to improve their non-original use property, satisfying the substantial improvement rules, via aggregation by purchasing other property so long as that property improves the functionality of the non-original use property being improved. The final regulations include an example of this through the acquisition and old hotel and then adding to the cost basis with installed gym equipment and restaurant-related property.

Other costs that are added to the basis of the property being improved include demolition costs, capitalized fees for development, required permits, necessary infrastructure, site preparation costs, and professional fees.

Vacancy Periods of Building or Structures to Meet Original Use Requirement

The May 2019 proposed regulations provided that, where a building or other structure had been vacant for at least five years prior to being purchased by a QOF or QOZB, the purchased building or structure would only then satisfy the original use requirement.

The final regulations instead made several taxpayer-favorable changes to this proposed rule. First, with respect to the property that was vacant beginning prior to the designation date of the QOZ through the date on which the QOF or QOZB purchased the property, only a one-year vacancy period will be required. Second, a three-year vacancy period is required for property that was not vacant at the time of the QOZ designation.

By Nick Gibbons